SQUIRREL VALLEY OBSERVATORY

by Randy Fllyn

Squirrel Valley Observatory MPC-W34 is a privately owned roll off roof observatory located in the foothills of western North Carolina. Major construction was completed in the summer of 2015 with equipment upgrades continuing to be made for private research and astrophotography. The observatory is the culmination of a life long dream. In September of 2016 the IAU Minor Planet Center assigned the observatory code, W34, to Squirrel Valley Observatory for it’s endeavors in the tracking and detection of minor planets, including hazardous asteroids and other Near Earth Objects. The primary mission of the observatory is astrometric research (the detection, confirmation and tracking of minor planets,ie hazardous asteroids, near earth objects, comets, and other various types of asteroids) and astrophotography work.

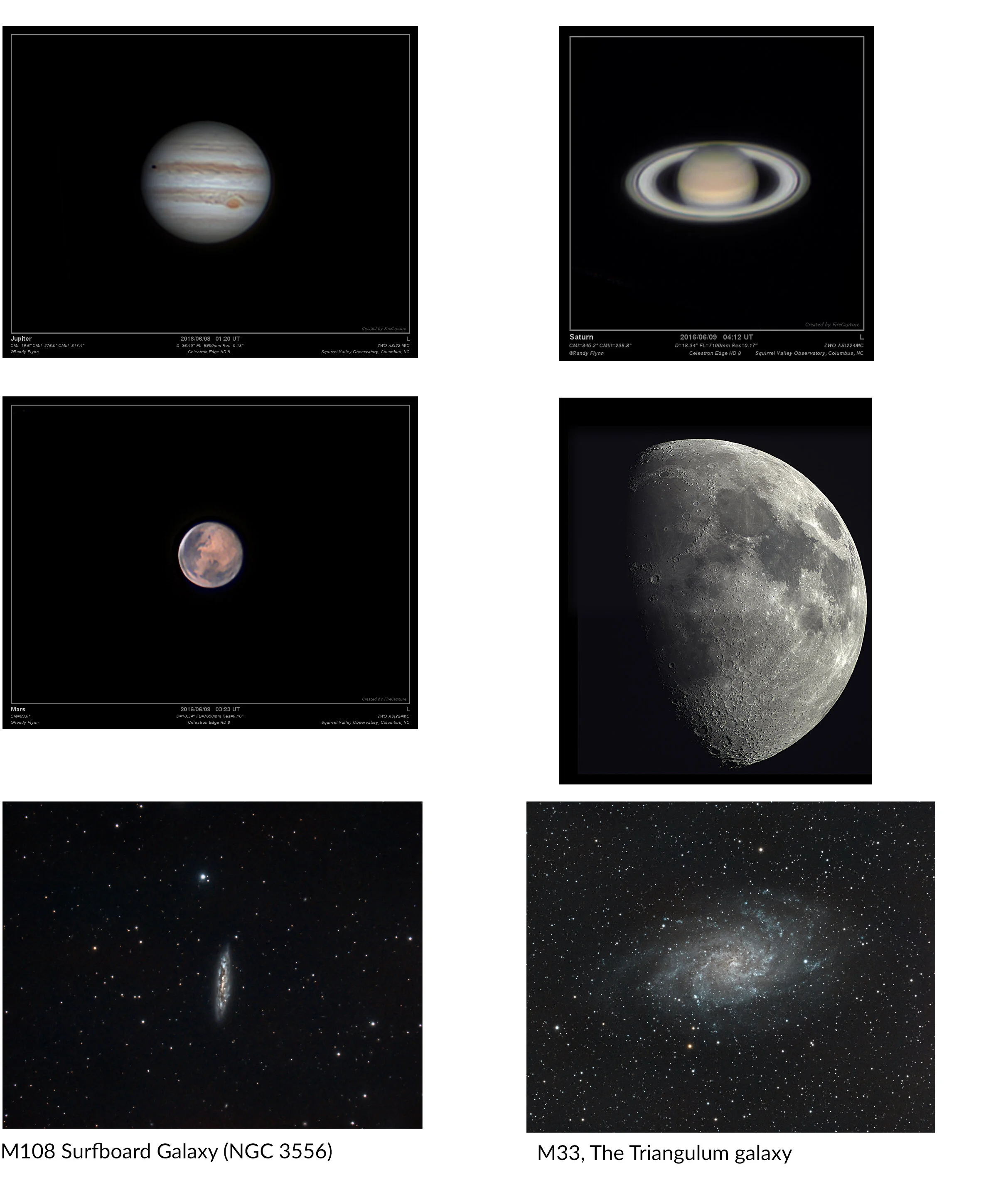

The observatory sends astrometric data to the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center on a regular basis, where is it used to help refine orbit predictions of various minor planet bodies. Each month the results are published in the minor planet circular. Additional research such as generating light curves for some of the larger exoplanets has also been carried out. The primary optical telescopes are rather modest in size, (a Celestron EdgeHD8 an Explore Scientific CF 127mm triplet refractor and an Explore Scientific 102mm triplet refractor), but with the addition of sensitive imaging cameras they can be used to detect, track and image very faint objects.

Each can be configured for planetary and deep sky imaging as well as visual observations. Our default configuration is an imaging setup used for asteroid astrometry and astrophotography. It is anticipated that minor planet astrometry, supernova detection and exoplanet research will continue to be the primary types of research conducted for the foreseeable future. Today even small facilities such as this are able to make important contributions to astronomical research.

The Celestron EdgeHD scope (8″ aplanatic schmidt-cassegrain), and the 127mm refractor are normally saddled on a side by side mount plate, which tracks the sky using a Losmandy G11/Gemini 2 system mount. This mount is in turn secured to a 12″ steel pier, bolted to an isolated concrete pier/footer. This setup minimizes much of the vibrations that are detrimental to long exposure imaging. An auto-guider is also used to provide for even longer

Celestron EdgeHD8 and Explore Scientific 102 mm triplet refractor on a tandem side by side saddle, mounted on a Losmandy G11/ Gemini 2 mount.

Explore Scientific 102mm APO Refractor mounted on AVX field tripod.

Current imaging configuration: Celestron EdgeHD8 and Ex- plore Scientific 127 mm triplet refractor. ASI 1600MM cool with electronic filter wheel and ASI 224MC cameras ahown.

exposures. An Explore Scientific 102mm triplet refractor is also available for field work on a portable Celestron AVX mount. The primary and secondary scope can be computer controlled from the observatory and from inside the connected warm room in my home. Additional portable telescopes are stored in the observatory. They include a homemade 10″ f5.6 reflecting telescope which is currently in a dobsonian mount configuration (grab and point). It is awaiting some upgrades and much needed maintenance.

The remaining instrument is a small, highly portable Meade ETX 80mm short tube refractor on a Meade goto mount. This is used as a grab and go scope for the brightest of objects and is not intended for serious imaging or research. There is also a Celestron 3″ “FirstScope tabletop reflector available for hands on public educational purposes.

Optical/Imaging

/Imaging telescope: Pier mounted Celestron EdgeHD8 aplanatic schmidt-cassegrain on a Los- mandy G11/Gemini2 mount.

Optical/Imaging telescope: Explore Scientific CF 127 mm F7.5 triplet refractor/w 0.7x reducer = f5.2.

Optical/Imaging telescope: Explore Scientific 102mm F7 triplet refractor/w 0.8x reducer = f5.6.

Additional optical telescopes: 10″ f5.6 Dobsonian reflector. (Currently offline for maintenance) Meade ETX-80mm AT-TC short tube refractor.

Field mount: Celestron AVX

Primary Deep Sky/Asteroid Imaging camera: ZWO ASI 1600MM Cooled Mono CMOS with Electronic Filter Wheel

Primary Deep Sky Imaging camera: ZWO ASI 294MC Cooled Color CMOS Secondary Deep Sky Imaging camera: Canon EOS T4i Primary Planetary Imaging camera: ZWO ASI224MC Autoguider camera: ZWO ASI120MM-S

I spend most of my observatory time acquiring astrometry data on minor planets,(primarily near earth astreroids) for the IAU Minor Planet Center. Astrometry is defined as "the science which deals with the positions and motions of celestial objects. Astrometry is now one of many fields of research within astronomy". (see here) So asteroid astrometry in its most basic definition is determining the position and track of an asteroid whether it is a main belt asteroid, near earth asteroid or any of the other classifications of minor planet.

While this is commonplace for many observatories and amateurs today and years past, what is not as common is the confirmations for new near earth asteroids that are made by small observatories. Near earth asteroids are those asteroids whose orbits could cause them to potentially pose a threat to earth at some point. So how does this work? Large government (and private) funded sky surveys (observatories) like Catalina Sky Survey PAN-Starrs ATLAS and Zwicky Transient Facility. As well a others scan and image large sections of the sky each night.

When they find an object that they can not identify, they immediately post their discovery observations for others to confirm. The Minor Planet Center maintains a web page for these discoveries called the NEOCP (Near Earth Object Confirmation Page). Observers like myself monitor this page for objects that are in their range (RA, Dec and magnitude) for observations.

As soon possible, we image the discovered object normally by taking multiple exposures, then using specialized software to stack the images and find the objects We record our observations and submit them immediately to the Minor Planet Center, providing that the residuals (precision and accuracy of data) is acceptable. This is all normally done within 24 to 72 hours of discovery. CNEOS the Center for Near Earth Object studies computes high-precision orbits for these Near-Earth Objects (NEOs) in support of NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office .

Once an orbit is determined, a designation is issued by the Minor Planet Center, the discover and observatories who helped confirm the object are then published in an MPEC (Minor Planet Electronic Circular). This is an example of an MPEC where Squirrel Valley Observatory W34 helped confirm the discovery of a new near earth asteroid designated 2019 FU (Apollo type) first observed by Catalina Sky Survey 703. MPEC 2019-F121 Granted all this is a somewhat simplified version of the process but accurate. So while all asteroid data submission is important, it is extremely satisfying for a small observatory using modest commercially available equipment to be able to contribute data that helps confirm the existence of a newly discovered near earth asteroid. In some cases even being the the 2nd, 3rd, 4th etc person to see this new object.

And while the images are not the pretty pictures that we often enjoy sharing, the data can be incredibly important. It is a way for the amateur to contribute real and meaningful data that assists the large multi-million dollar sky surveys with huge budgets. To date SVO has submitted data on nearly 1,400 asteroids, about 400 of those being near earth asteroids, but most importantly we have directly helped confirm over 120 near earth asteroids since 2017. All this with an 8 inch scope, a CMOS camera and a Losmandy G11 mount.

The logs of my asteroid observations can be found by clicking the Minor Planet Research tab at the top of the SVO webpage or by clicking on the image of the log on the right side of that page. Alternately you can follow this link. http://svo.space/astrometry/

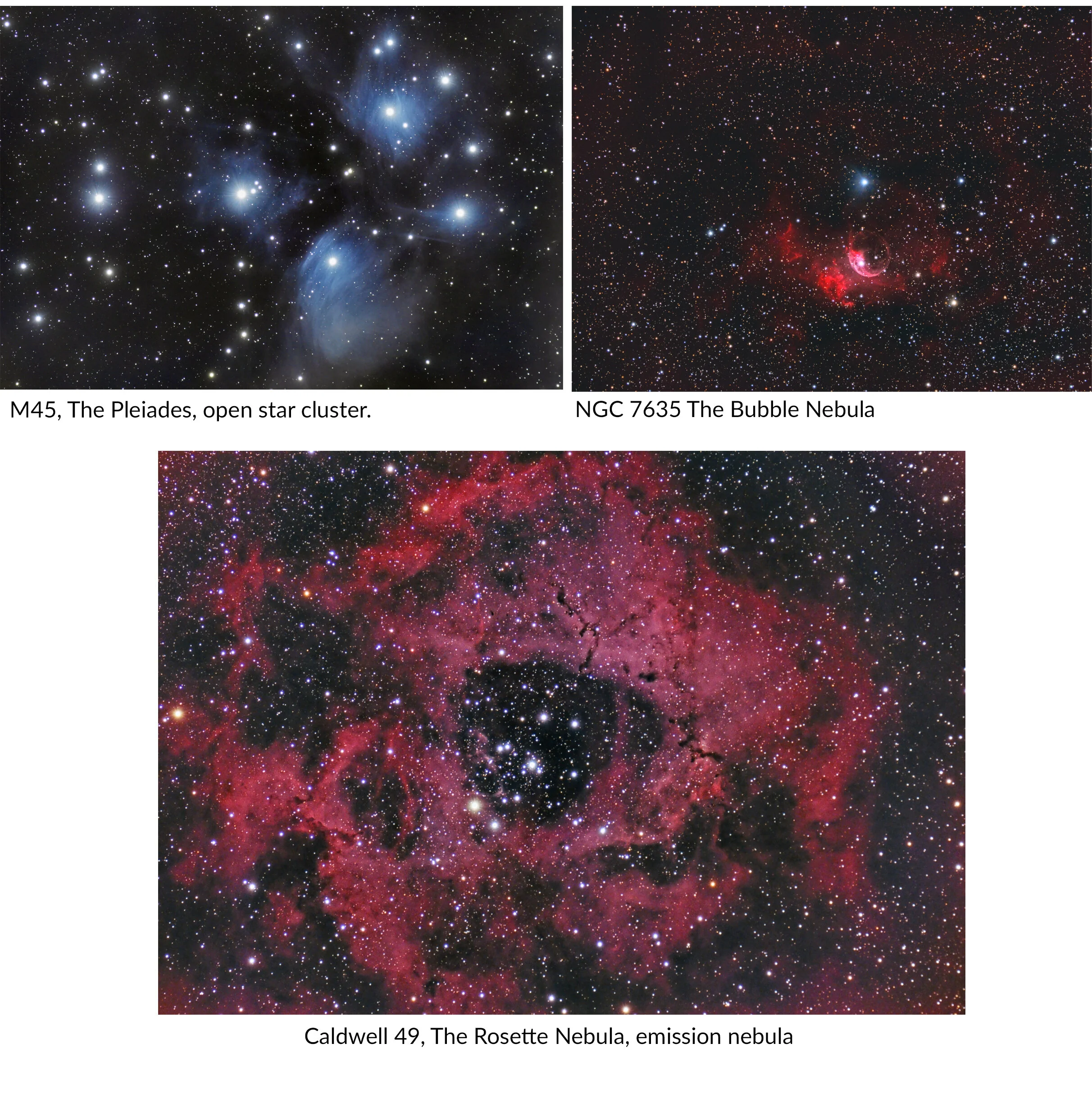

Imaging

Astronomy has been my hobby and passion for over 40 years. Most of that time was spent on visual astronomy and public outreach. Only in the last 5 years did I begin to fully delve into digital imaging. This is about the same time I built a roll off roof observatory.

I am a member of the following organizations: “American Astronomical Society”, “The Society for Astronomical Sciences”, “The Astronomical League”, “Astronomers Without Borders”, “NASA Night Sky Network” and the “Astronomy Club of Asheville” in North Carolina. My astrobin page is here: http://www.astrobin.com/users/ncwolfie/ I enjoy seeing how in most cases images have improved from the first to the last. I purposely leave the older unpolished images online for that reason.

Squirrel Valley Observatory has sponsored several outreach events for the public and local school systems over the years.

I use Pixinsight processing software now for all of my image processing. In fact my biggest influence in digital astrophotography has been Warren Keller, author of "Inside Pixinsight". Then there is, Harry’s Astroshed and Light Vortex which were and continue to be tremendous aids when using Pixinsight. I refer back to their guides constantly when processing images. Pixinsight processing software changed everything for me.

Before Pixinsight, I used Deep Sky Stacker, a very capable stacking software, and then Photoshop for processing. When I first started out with Deep Sky Stacker, it was Doug German’s Budget Astro tutorials that were instrumental in providing a clear explanation for the basics of image processing. I have two main belt asteroid discoveries pending at Squirrel Valley Observatory, 2017 SR9 and 2017 DV8. Both will take some considerable time and effort to confirm with my current setup due to the fairly long orbital periods and magnitude.