Peter Goodhew Recently retired after a lifelong career working for IBM. Living in West London under the app- roach path to Heathrow airport with extreme light pollution.

In the beginning:

As a child I would look up at the night sky in awe of what I could see - wondering what might he going on up there in this unexplored universe. I recall as a schoolboy going to the public library with my younger brother and borrowing every book that they had on astronomy. My interest developed further in my teenage years, encouraged by watching Patrick Moore’s monthly television program, The Sky At Night, on the BBC. The program continues to this day, and included my image of M51 in an episode earlier this year.

When it was time to go to university there weren’t many degree courses in astronomy available and so I read physics and mathematics at Exeter University. Similarly, after graduating I accepted that careers in astronomy were few and far between - and weren’t particularly well paid then. So instead of becoming a professional astronomer I pursued a career in IT with IBM. Around five years ago a friend had bought his first telescope and started showing me some of the images that he had taken. I was in awe at what he showed me - even though they were done with just a small refractor and a DSLR. Inevitably I had to get a telescope and camera of my own, with his advice and guidance. My first telescope was a 4 1/2” refractor, on an AZ/EQ6 Mount and tripod - with a Canon DSLR. Naively I thought I could just stick it in the garden, point it at the sky, and start taking photographs.

The learning curve was steep - and painful - with things such as polar alignment, guiding, image calibration, stacking and processing being far more complicated than I had ever imagined. This, coupled with the rarity of clear skies with the British weather, meant that the first year was intensely frustrating. On more than one occasion I was very close to selling up everything and abandoning astrophotography as a hobby. However seeing for the first time in my life the craters on the moon, the rings of Saturn, and the moons of Jupiter helped me persevere.

Eventually I was producing very basic images of galaxies such as M51 or the Leo Triplet - and very proud of them (even though they were pretty much devoid of any detail). I started digging into my wallet and had a roll-off roof observatory installed in my garden. This meant I didn’t have the hassle of setting up and breaking down the rig every time the clouds cleared. Being more productive I then took the leap into CCD cameras and filter wheels with a QSI683wsg8 camera.

IC1396A - Elephant's Trunk Nebula

The Elephant's Trunk nebula is a concentration of interstellar gas and dust within the much larger ionized gas region IC 1396 located in the constellation Cepheus about 2,400 light years away from Earth.[The piece of the nebula shown here is the dark, dense globule IC 1396A; it is commonly called the Elephant's Trunk nebula because of its appearance at visible light wavelengths, where there is a dark patch with a bright, sinuous rim. The bright rim is the surface of the dense cloud that is being illuminated and ionized by a very bright, massive star (HD 206267) that is just off the right hand edge of the image. The entire IC 1396 region is ionized by the massive star, except for dense globules that can protect themselves from the star's harsh ultraviolet rays.

The Elephant's Trunk nebula is now thought to be a site of star formation, containing several very young (less than 100,000 yr) stars that were discovered in infrared images in 2003. Two older (but still young, a couple of million years, by the standards of stars, which live for billions of years) stars are present in a small, circular cavity in the head of the globule. Winds from these young stars may have emptied the cavity. The combined action of the light from the massive star ionizing and compressing the rim of the cloud, and the wind from the young stars shifting gas from the center outward lead to very high compression in the Elephant's Trunk nebula. This pressure has triggered the current generation of protostars. This is a 2-panel mosaic. 47 hours total integration. RGB each 10x300s, Ha 26x900s, OIII 20x900s APM TMB 152 F8 LZOS, 10 Micron GM2000HPS, QSI6120ws8.

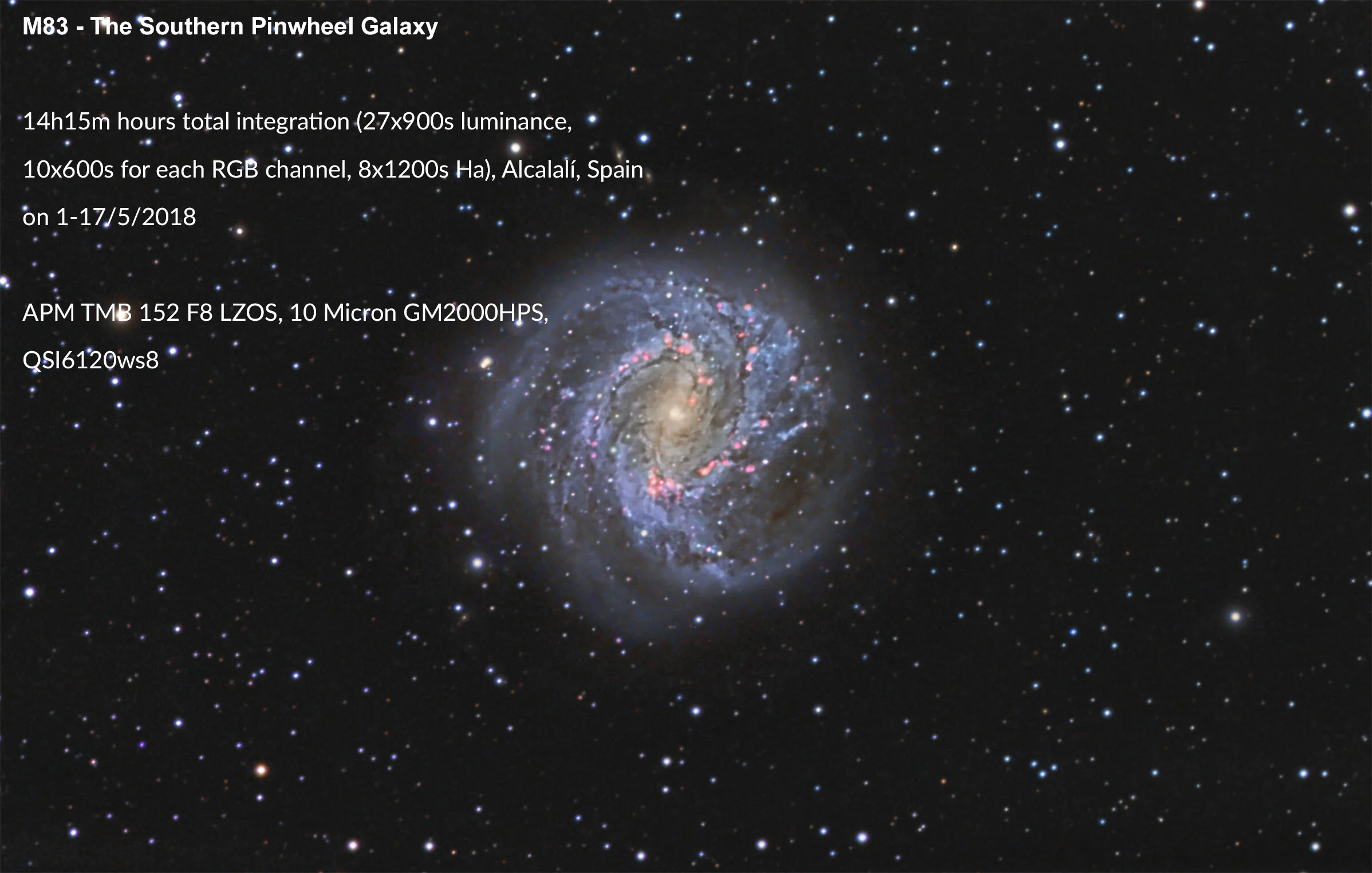

However the more that I progressed the more I got frustrated with the limitations of imaging from London. After visiting an astronomy holiday location in southern France it became obvious that I needed to establish a robotic remote observatory at dark site somewhere in Europe. I ended up choosing southern Spain where there are around 270 clear nights a year (in contrast to more than 270 cloudy nights in London!). I used a hosting site and acquired even better equipment: An APM 6” refractor with Russian-made LZOS glass, a 10 Micron GM2000 HPS Mount, a QSI 6120ws8 CCD camera and a set of Astrodon filters. This totally transformed my astrophotographic capabilities and I was now producing publishing-grade images. Having learnt the value of going deep both in terms of length and quantity of exposures I decided to upgrade at the beginning of this year to a dual rig.

I duplicated my remote setup with twin APM 6” LZOS refractors, dual QSI 6120 CCD cameras, and another set of Astrodon filters - all sitting on my 10Micron GM2000 Mount. I have my own robotic observatory with a roll-off roof and everything is fully automated and robotic, based on Sequence Generator Pro. Images are sent to my PC at home throughout the night and are ready for me to process when I wake up in the morning. Meanwhile my observatory in London has been reconfigured to do lunar and planetary imaging that isn’t as affected by light pollution and doesn’t require hours of clear nights. Occasionally I also use it for the cores of very bright planetary nebulae. I now have a Celestron C11 sitting on a 10Micron GM2000 and am making my first forays into cooled CMOS imaging.